Coronaviruses have caused widespread disease in humans, including SARS CoV-1, MERS and most recently the global COVID-19 pandemic.

The recent new findings, published in the journal PLOS ONE, will help understand the diversity of coronaviruses in bats and inform global efforts to detect, prevent and respond to infectious diseases that may threaten public health, particularly in light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the researchers from the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute in the US, studies will evaluate the potential for transmission across species to better understand the risks to human health.

They said the newly discovered coronaviruses are not closely related to coronaviruses Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS CoV-1), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) or SARS-CoV-2.

“Viral pandemics remind us how closely human health is connected to the health of wildlife and the environment,” said Marc Valitutto, former wildlife veterinarian with the Smithsonian’s Global Health Program, and lead author of the study.

“Worldwide, humans are interacting with wildlife with increasing frequency, so the more we understand about these viruses in animals what allows them to mutate and how they spread to other species the better we can reduce their pandemic potential,” Valitutto said.

Researchers detected these new viruses while conducting surveillance of animals and people to better understand the circumstances for disease spillover.

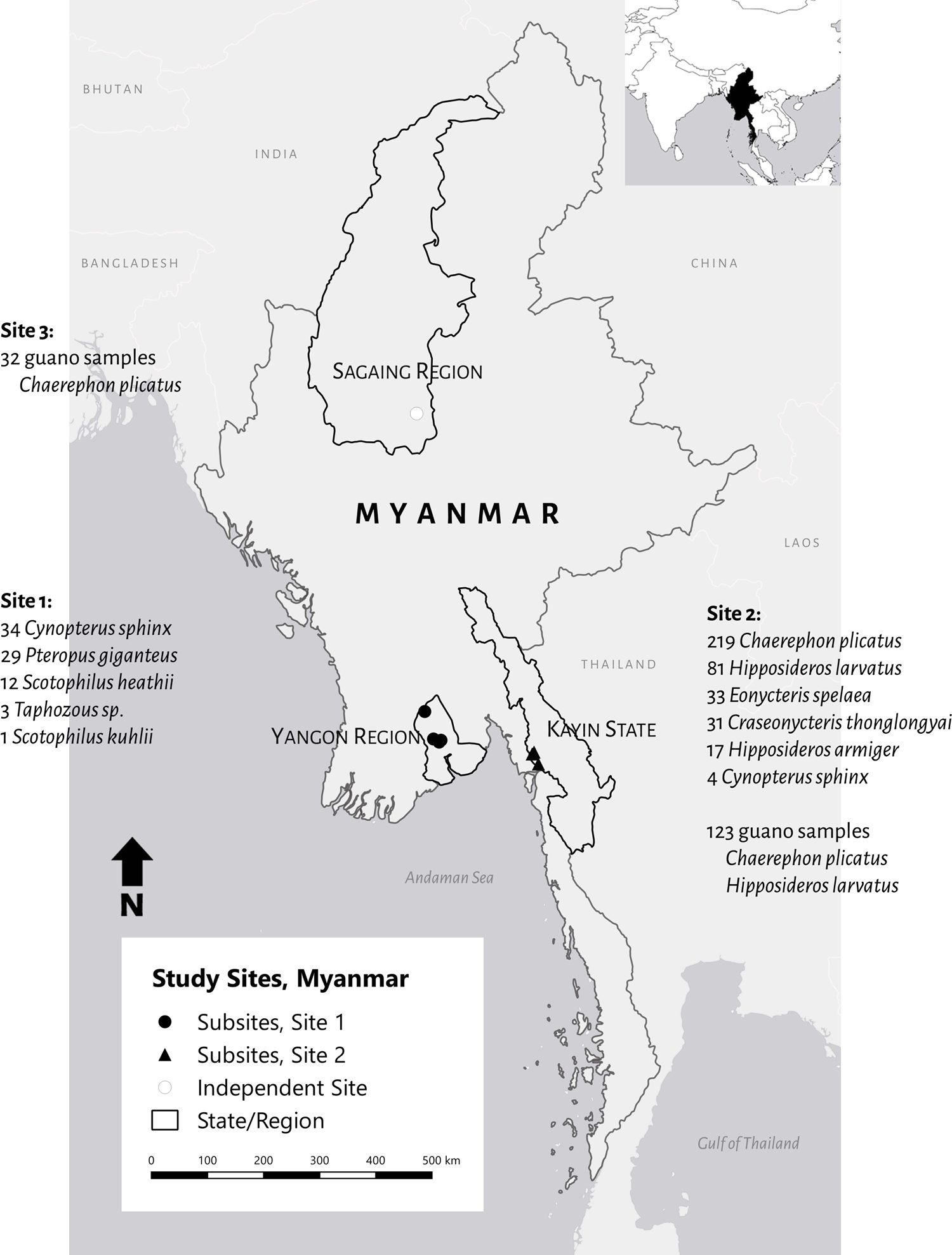

The team focused their research on sites in Myanmar where humans are more likely to come into close contact with local wildlife due to changes in land use and development.

From May 2016 to August 2018, they collected more than 750 saliva and faecal samples from bats in these areas.

Experts estimate that thousands of coronaviruses many of which have yet to be discovered are present in bats.

Also Check for Live updates : Corona Live Updates From Splco – Source WHO

Researchers tested and compared the samples to known coronaviruses and identified six new coronaviruses for the first time.

The team also detected a coronavirus that had been found elsewhere in Southeast Asia, but never before in Myanmar.

The researchers said these findings underscore the importance of surveillance for zoonotic diseases as they occur in wildlife.

The results will guide future surveillance of bat populations to better detect potential viral threats to public health, they said.

“Many coronaviruses may not pose a risk to people, but when we identify these diseases early on in animals, at the source, we have a valuable opportunity to investigate the potential threat,” said Suzan Murray, director of the Smithsonian’s Global Health Program and co-author of the study.

“Vigilant surveillance, research and education are the best tools we have to prevent pandemics before they occur,” Murray said.