India country’s first lithium reserve, found in Jammu and Kashmir, is of the best quality, a senior government official told PTI

The 5.9-million ton reserve of lithium, a crucial mineral for the manufacturing of electric vehicles and solar panels, had been discovered in Reasi district by the Geological Survey of India (GSI).

Lithium is a chemical element of Periodic Group 1 (Ia), the alkali metal group, and the lightest of the solid elements. The metal itself, which is soft, white, and shiny, as well as several of its alloys and compounds, are manufactured on a large scale.

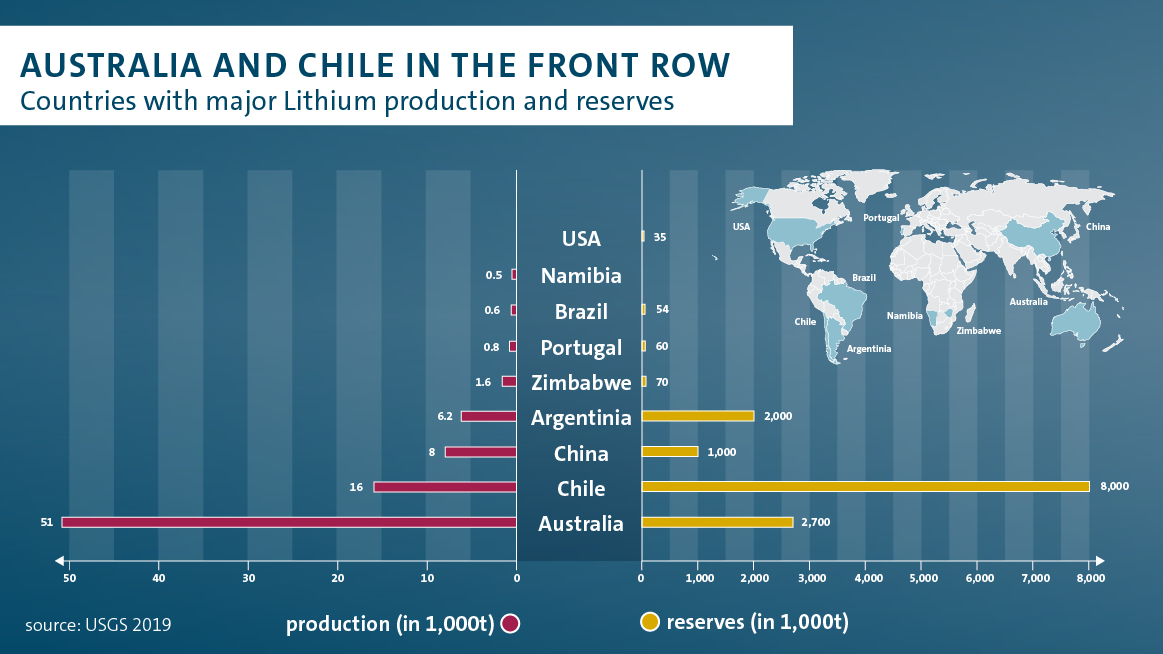

According to a report by Volkswagen, the global market for lithium is expanding quickly. Annual production in the top producing countries increased from 25,400 to 85,000 tonnes between 2008 and 2018.

Its usage in electric vehicle batteries is a significant growth driver. However, lithium is also used in laptop and cell phone batteries, as well as in the glass and ceramics industries, the report says.

“Lithium falls in the critical resource category which was not earlier available in India and we were dependent for its 100 percent import. The G3 (advanced) study of the GSI shows the presence of best quality lithium in abundant quantity in the foothills of Mata Vaishno Devi shrine at Salal village (Reasi),” J-K Mining Amit Secretary Sharma told PTI.

According to data compiled as of June 3, 2022, Bolivia had the most lithium deposits, followed by Chile, Australia, China, and Argentina, according to SPglobal.

An India’s first large lithium discovery, with the sole other reserves being a minor 1600-tonne deposit identified in Karnataka two years ago also increases the supply position in the days to come .

Until now, the country had relied on Australia, Chile, and Argentina for any lithium imports required for its manufacturing sector. But because refining lithium ore into a material that can be used to produce batteries is a difficult process, India will continue to rely on imports for at least a few years, the Quartz report says.

Sharma said against the normal grade of 220 parts per million (PPM), the lithium found in Jammu and Kashmir is of 500 ppm-plus grading, and with a stockpile of 5.9 million tons, India will surpass China in its availability.

Asked about the possible timeline for its extraction to start, Sharma said every project takes its own time. “We had G3 level study and it will now be followed by G2 and G1 study before the final extraction of the metal.”

“The local youth, whether skilled, semi-skilled or unskilled, will be part of this project. People who will be affected by this project will be adequately compensated and rehabilitated under rules,” he said.

Australia comes from ore mining, while in Chile and Argentina lithium comes from salt deserts, so-called salars.

The extraction of raw materials from salars functions as follows: lithium-containing saltwater from underground lakes is brought to the surface and evaporates in large basins.

The remaining saline solution is further processed in several stages until the lithium is suitable for use in batteries.

There are always critical reports on the extraction of lithium from salars.

In some areas, locals complain about increasing droughts, which for example threatens livestock farming or leads to vegetation drying out.

From the point of view of experts, it is still unclear to what extent the drought is actually related to lithium mining. It is undisputed that no drinking water is needed for the lithium production itself.

What is disputed, on the other hand, is the extent to which the extraction of saltwater leads to an influx of fresh water and thus influences the groundwater at the edge of the salars.

In order to assess this, the underground water flows in the Atacama Desert in Chile, for example, have not yet been sufficiently researched.

In addition to lithium mining, possible influencing factors include copper mining, tourism, agriculture and climate change.