…

In the backdrop of the Cold War and a perceived threat of strikes from space, both the United States and the erstwhile USSR worked on the Anti-Satellite Weapons (ASAT) programme, back in 1959.

It is the background Sixty years later, India conducted its first anti-satellite missile test.

In a specially televised announcement on Wednesday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India has become the fourth country after the US, the USSR and China to have used such a weapon, and have successfully destroyed a low earth orbit satellite in space using a missile which covered a distance of 300 km to engage the target. It was called ‘Mission Shakti’.

While the government claims that the ASAT test has provided ‘credible deterrence’ against threats to space-based assets from long-range missiles, but a former ISRO Satellite Communication Engineer N Kalyan Raman, who has worked with ISRO for over two decades said that this won’t be effective at all.

“Most of the countries’ satellites are in the higher orbit, and even with this India won’t be able to knock out those satellites,” he said. He added that it cannot be an “effective spy satellite”.

According to Raman, this kind of ‘deterrence’ doesn’t quite add up because as he puts it, “Not only will you be spending a lot, the enemy can always hit you.”

He also pointed out that there are various effective ways to spy on your enemy, and the anti-satellite weapon doesn’t quite help in it.

“In a war like situation, if a country wants to spy on its enemies there are various ways to do it for example, Google Earth. All you need is good resolution photos. Why do we even need this?” he asked.

Raman said that the anti-satellite test was more a demonstration of India’s ballistic missile defence system, rather than its ability to challenge its adversaries in space.

“Most medium and long-range ballistic missiles reach apogees well above 300 kilometres, and it’s not that simple to destroy them,” he added.

This anti-satellite weapon demonstration has a long history. It first came into existence in the Cold War/Space Race era, 1985 was the last time that the United States had used an anti-satellite system to destroy its P-781 satellite that had instruments aboard to study solar radiation.

“Then was a paranoid situation. We don’t live in those times anymore,” Raman said. He said that if this was an effective tool in winning wars other countries would be interested in developing them too. But, they aren’t.

He also said that space is occupied by multiple satellites of many countries. “The ASAT weapon won’t give any strategic advantage, no country is dependent on one satellite,” he said.

“This is is just about optics. It’s a part of the aggressive posture, this is just telling the country that we have muscle,” he added.

Having worked with ISRO for over two decades, Raman also lamented on how the space research organisation has changed its art of work.

“ISRO has done such great work they have always been associated with peacebuilding efforts. Now to be associated with this anti-satellite is simply distasteful.” Although the Prime Minister emphasised that the test did not alter its commitment against the weaponisation of outer space, Raman said, “To mix warlike activity with ISRO is repulsive”.

Vipin Narang, an associate professor of political science at MIT, said while China can knock out all of India’s satellites India cannot do the same to China. “So it’s kind of a weird balance for India if it’s interested in getting into the anti-satellite deterrence game,” he said.

India had acknowledged back in 2012 that it had the “building blocks” for ASAT technology, and it has since tested ballistic missiles that have that capability.

However, this most recent test is the first time that India actually intercepted a satellite with one of its missiles.

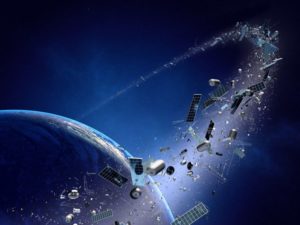

Meanwhile, acting U.S. Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan has warned any nations contemplating ASAT weapons tests, like the one India carried, risk making a “mess” in space because of debris fields they can leave behind.

Vikram Ambalal Sarabhai, an Indian scientist and innovator widely regarded as the father of India’s space programme, had once said, “There is a real danger that developing nations may adopt a space programme largely for the glamour, devoting resources not through a recognition of the values of which we are talking about here, but from a desire to create a sham image nationally and internationally.”

Both DRDO and ISRO are brain child of then Congress Prime Minister Nehru whose Contributions in Space and Science field is immensely appreciated by many cutting across the parties in india.