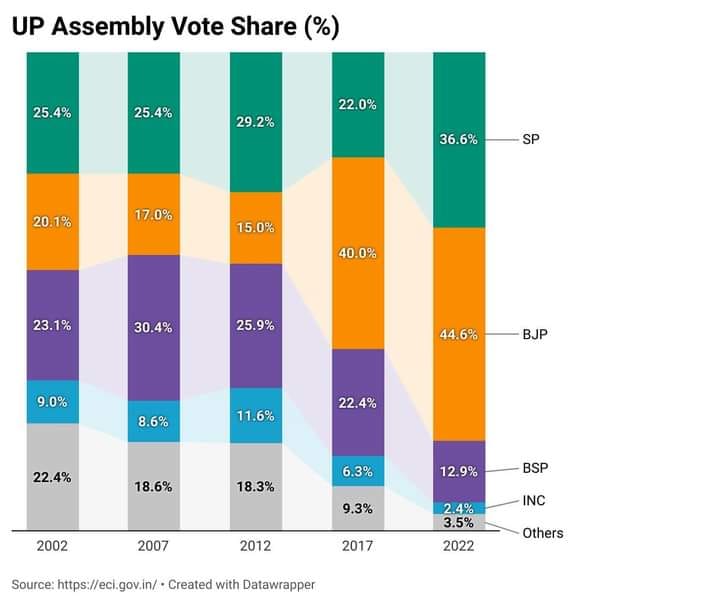

The fact remains that despite the discontent on the ground, BJP received more than 41% votes while its allies too polled around 4% votes more.

As a result under the leadership of Yogi , in uttarpradesh BJP has managed to add more votes to its kitty than 2017 when it secured a 39.67% vote share in the state.

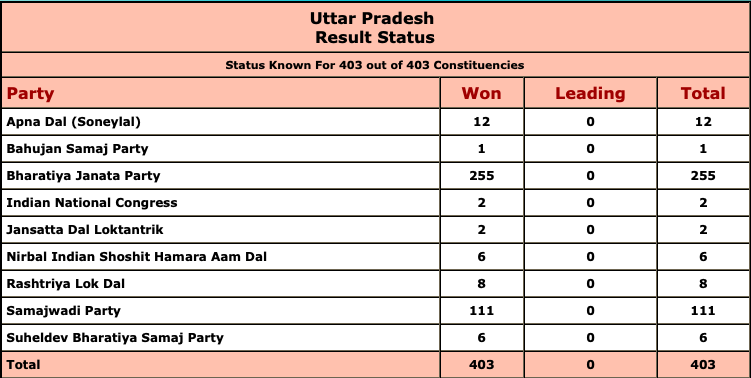

Political assessment that the opposition in UP was decimated is wrong.

Samajwadi Party actually polled around 32% votes, around 10% more than what it had polled in 2017 and around 3% more than in 2012 when the party had secured an absolute majority.

The RLD also polled 2.86% votes and its other allies PSP, SBSP, Janvadi Party, Apna Dal (K) and NCP 3% of the votes.

While the Election Commission’s role certainly needs scrutiny, Samajwadi Party should also look for where it failed to capitalise on the opportunity when all the conditions were in its favour.

Samajwadi Party and its leader Akhilesh Yadav did misread the importance of Congress and BSP in the state, writing off both.

He committed the same mistake he did in 2017 i.e. turning the state election into a bipolar contest.

His mathematics was simple. Muslims plus Yadav, Jat, Gujar, Maurya, Pasi, Kurmi and some other OBC castes will consolidate behind him and he will touch the majority mark.

In the process he appears to have alienated both forward caste and Dalit voters.

While BSP and its chief Mayawati ran a low decibel campaign, Samajwadi Party sold the narrative that BSP no longer mattered.

The results have proved him wrong. BSP and SP votes together have actually exceeded the votes polled by the BJP.

Dalit voters were pushed towards the BJP as they felt threatened at the prospect of the return of Yadav, Jat, Gujar, and Kurmi voters to power, the social groups which historically oppressed them.

Mayawati also left no effort to ruin the prospects of the Samajwadi Party.

The BSP offered ticket to all those denied an opportunity to contest by the Samajwadi Party.

At least 50 such candidates, mostly Muslim and Yadavs, not only proved to be spoilers for SP but also helped BJP to close the gaps it needed to divert people’s anger.

But this mandate is not an end of the road for opposition parties. It has opened the doors for new possibilities.

They can actually rejoice at the return of so many voters they had lost to BJP in 2014, 2017 and 2019 elections.

It is time to build a new momentum from here. The opposition parties should not lose time in setting their own house in order, get their voters enrolled on voters’ lists and cobble new social alliances.